If I ask you what you will be doing 10 minutes from now, you can probably give me an accurate answer.

But what if I ask about your plans in 10 months? It’s unlikely that you know for certain. What about 10 years from now? That would be almost impossible to answer, right? You know far more about the present than the future.

Ironically, the exact opposite is true in the world of investing. Investors have no idea what tomorrow will bring, or the next 6 months, or even this year. But over long time horizons, investment returns are increasingly predictable.

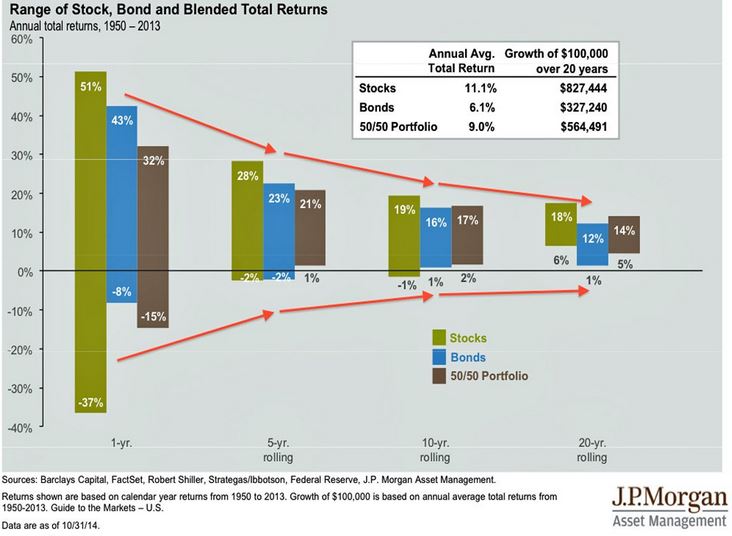

Consider this graph created by J.P. Morgan:

This graph shows 63 years of stock (green) and bond (blue) returns. The brown bar is a 50% stock, 50% bond portfolio. Notice the important details:

- Over short periods of time, returns vary dramatically. Stocks are much more volatile than bonds, and within a one-year investment horizon, the range of historical stock returns is very wide, from a 51% gain to a 37% loss.

- Over long investment periods, risky investments become far more consistent and the range of returns is more narrow.

- Over a five-year horizon, things look very different. The worst rolling five-year period delivered a 2% loss for stockholders, and a 1% gain for a 50/50 portfolio.

- Over 25 years (a time period more appropriate for young investors), stock investors do even better. The range of returns narrows further – from a maximum gain of 18% per year to a worst case gain of 6% per year.

The tendency for risky investments to become safer over time is known as time diversification. Assuming future asset returns are loosely correlated with past returns, the implication is that rational investors should hold investments for long periods of time.

Investors are rewarded for patience and staying invested in the market over long periods of time.

The Ugly Truth

Unfortunately, most investors fail to embrace a long-term mentality, which results in costly mistakes.

As I pointed out in my critique of stock picking, investors who trade frequently do very poorly. The most active traders significantly underperform a simple buy-and-hold index strategy.

Vanguard and Fidelity have fielded studies to test the relationship between investor performance and trading frequency. Both companies found that top-performing investors do very little to nothing with their investment portfolio. They purchase low-cost funds, and remain invested for the long haul. Fidelity found that many of the highest performing investors forgot about their accounts entirely.

Professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean have done excellent work on this topic. In their paper, “The Behavior of Individual Investors,” they review and summarize the vast amount of research on the stock trading behavior of individual investors. Their findings are remarkable:

Individual investors:

- Are overconfident in their ability

- Underperform standard benchmarks (e.g., low cost index funds)

- Sell winning investments while holding losing investments (the “disposition effect”)

- Are heavily influenced by limited attention and past return performance in their purchase decisions

- Engage in naïve reinforcement while trading

- Tend to hold undiversified stock portfolios

Statistician Nate Silver illustrates a similar point in his book, “The Signal and the Noise,” through the following finding:

“In the 1950s, the average share of common stock in an American company was held for about six years before being traded — consistent with the idea that stocks are a long-term investment. By the 2000s, the velocity of trading had increased roughly twelvefold. Instead of being held for six years, the same share of stock was traded after just six months. The trend shows few signs of abating: Stock market volumes have been doubling once every four or five years.”

Many investors have bought into the overwhelming financial noise, choosing to follow the advice of brokers, salesmen, and media pundits while refusing to acknowledge the compelling evidence against frequent trading.

Less is More

In our modern society, less is almost never more. We are constantly under pressure to work harder, faster, and longer. Consider a few common examples:

- To get promoted, you are supposed to work longer hours and accept additional responsibilities.

- To gain more knowledge, you must read/listen to more inspiring content.

- To get fit, you need to exercise consistently.

But what about the investment world? The data and research paint a clear picture – less really is more.

A long-term mindset and a couple of well-diversified index funds are the only requirements for investment success.